India’s $10 Trillion Journey Runs on Batteries

Why India must build its own lithium-ion ecosystem?

India’s path to a $10 trillion economy depends on one thing most people never think about: Batteries. With nearly 80% of its oil & half its natural gas coming from abroad, our energy bill has become a drag on economic ambition and even strategic independence. Recent trade skirmishes with the US around energy supply have shown how vulnerable the system is.

But this challenge has a silver lining. India can now build a homegrown lithium-ion ecosystem from the ground up. A 400 GWh cell manufacturing industry can create almost $80 Bn in market cap, roughly equal to India’s entire listed auto ancillaries space today. This is where the opportunity lies. To explore the full thesis, check out the video below or read the summarised version in our blog:

In this edition of Singularity One, we focus on four ideas:

How battery demand is evolving, driven by EVs & grid storage

How China built an unbeatable supply chain

What India is doing through policy to catch up

Where investment opportunities lie in the next 5 years

At Singularity, we have deployed ~$200 Mn in the past eight years, backing founders with ambition, early conviction, and strong execution, especially in sectors shaping India’s energy transition. Our Operator-Investor framework is supported by Singularity Plus, a network of specialists in policy, technology, capital markets, and deep industrial domains.

While we invest across solar, transmission and distribution, biofuels, and commercial EVs, the area that excites us most today is batteries & battery materials. It blends high strategic importance with a decade-long investment super cycle.

Why Batteries Matter Now?

Batteries power everything around us. From the camera recording the above video to the phone or laptop you might be reading this, lithium-ion chemistry has quietly become the backbone of modern life. In 2019, the Nobel Committee called lithium-ion batteries one of the greatest gifts to humankind and a cornerstone for a world beyond fossil fuels.

The global EV market has hit an inflection point. Battery prices have fallen by half in the last 2 years, shrinking the upfront cost gap with petrol vehicles. When buyers account for fuel savings and lower maintenance, EVs start becoming the cheaper option. In commercial categories like buses, delivery fleets, and taxis, payback can be as short as two or three years.

All this means is that EV penetration across categories will rise significantly, which in turn will drive big chunk of the demand for lithium-ion batteries.

Global EV Penetration: China Leads, Others Follow

China crossed a milestone last year where more than half of new vehicle registrations in some months were EVs or plug-in hybrids. Supply has exploded, giving consumers real choice across segments.

The US & Europe are at different stages, but both have seen a consistent increase in adoption over the last five years. The four drivers that unlock EV growth:

• Expanded supply

• OEM cost reductions

• Strong regulatory commitment

• Supportive ecosystem led by charging infrastructure & upstream materials

Where India Stands?

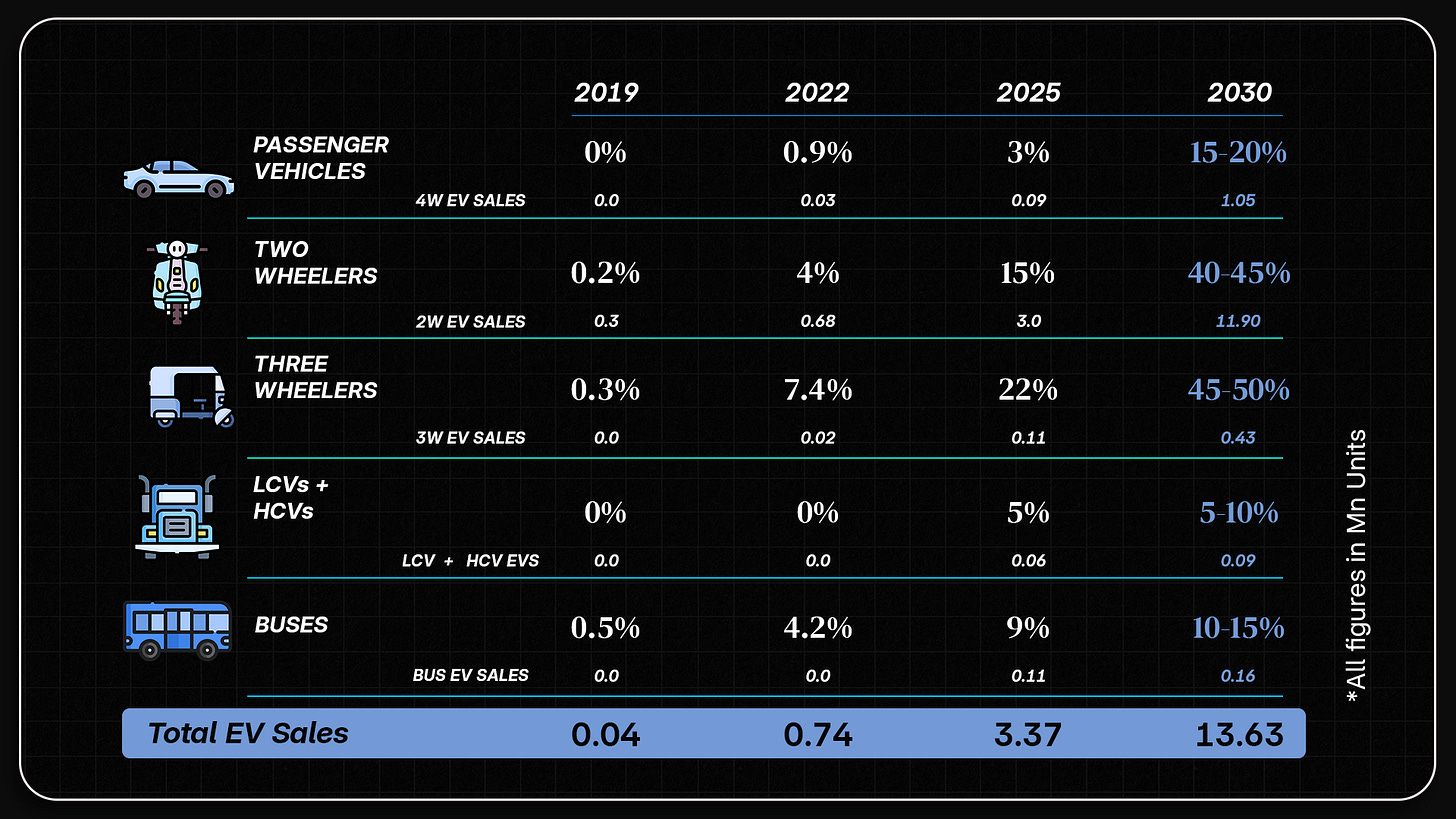

In India, the story is unfolding sector by sector.

Two-wheelers: By 2030, EVs could form one third to half of the market. Scooters already make up 37% of total two-wheeler sales and are leading electrification. EV bikes will follow the same curve with a slight lag.

Four-wheelers: Penetration is around 3-5% today, but could reach at least 20% by 2030, driven by supply expansion and urban use cases. Growth depends heavily on the pace of charging infrastructure roll out.

Buses: India has quietly become a global leader in electric buses. Almost all new state transport tenders are now electric, and adoption is rising in both public and private segments.

India has already emerged as global leader within three-wheeler category India and electric trucks (LCVs + HCVs) are starting to show early green shoots. Across mobility, India will need more than 100 GWh of lithium-ion cells annually by 2030. Including stationary storage, this could rise to 130-150 GWh.

Why Storage Is Now a Grid Necessity

The need for grid-scale storage is no longer a theoretical concept. As renewable expand, they introduce variability that the grid must absorb.

A standard rule of thumb: for every gigawatt of solar and wind added, the grid needs around one gigawatt-hour of storage.

To meet India’s 500 GW renewable target, the country will need 250-300 GWh of storage capacity as well by 2032. More than 60 GWh of storage tenders have already been announced in the last 18 months, with 10 GWh under construction.

This is India’s storage moment.

At the same time, new applications like autonomous vehicles, delivery drones, industrial robotics, and edge AI are demanding high-density, lightweight batteries with better thermal performance. Autonomous vehicles can consume between 15 and 30% more energy because of onboard compute.

The global battery market is projected to grow from 1500 GWh to 4500 GWh by 2030.

India’s annual requirement will be around 150 GWh. Imports of fully built packs already cost around $1 to $1.5 Bn a year. Without localisation, this number could climb to $15 Bn.

This is the value we must capture domestically.

What India Can Learn from China’s Playbook

China’s rise wasn’t an accident. To break down this journey, we were joined by Alex Xie, Partner at BCG, who specialises in China’s automotive industry.

China began with a weak automotive sector. Foreign joint ventures brought in capital, talent, and technology, and domestic private companies soon emerged, often hiring veterans from these ventures.

The government recognised two realities that China depended heavily on imported energy, and catching up with global OEMs in internal combustion technology was nearly impossible. Therefore they made a decisive bet on EVs that included:

• Incentives for local battery companies

• A whitelist that ensured EV subsidies applied only to vehicles using locally produced batteries

• Scale-driven competition to drive down costs

• Tight alliances between OEMs and battery makers

Over time, this built the world’s largest and most integrated battery supply chain.

India does not need to replicate China, but we can borrow the underlying logic:

Tie industrial policy, capital, technology, & long-term scale into one coordinated push.

Breaking Down the Battery Supply Chain

A lithium-ion battery is built on five core layers: the cathode, the anode, the separator, the electrolyte, and the casing. Most of the value sits in the cathode, which contributes nearly 25% to 40% of the total cell cost, while the anode adds another 10% to 15%.

These two components drive performance and chemistry decisions, and anchor the economics of the entire chain. The process starts with mining and refining minerals like lithium, nickel, cobalt, and graphite, after which these inputs are converted into cathode and anode active materials. This step is technically demanding & concentrated among a handful of global players. The active materials then move into cell manufacturing, where electrodes are coated and assembled into cylindrical, prismatic, or pouch cells.

Packs are built next with thermal systems and battery management software, and finally, recycling feeds recovered materials back into the upstream stages. As the market matures, this loop will become essential for reducing dependence on mined commodities and stabilising supply for large-scale energy storage and EV demand.

Midstream: India’s Strategic Opportunity

The solar industry offers a clear analogy. In 2018, China controlled 95% of global solar processing. India had around 3 GW of domestic module capacity.

With policy support such as Basic Customs Duty, Approved List of Models and Manufacturers, and Production Linked Incentive, India is now set to reach:

• 150 GW of module capacity

• 75 GW of cell capacity

• $3 Bn annual profit pool

• $15 Bn in new market cap created in just five years

And this could double by 2030!

Now, same playbook applies to batteries. India is targeting around 130 GWh of domestic cell capacity by 2030. This requires $12–14 Bn in capex across the chain, with about $8–9 Bn for cell and pack manufacturing & $4–5 Bn for midstream materials like cathode, anode, electrolyte, and separators.

Players across the chain include Exide, Amara Raja, Ola Electric, Reliance, JSW Energy, HEG, Lohum, Epsilon Carbon, Himadri Chemicals, Gujarat Fluoro, Neogen, and Altmin. Some, like Epsilon and Gujarat Fluoro, are setting up capacities in the US as well.

Cell manufacturing is low margin, pack assembly is even thinner. Midstream offers pricing power, technology differentiation, and better profitability. We estimate around $1 Bn in annual profit pools, roughly $20 Bn in market cap creation on $4 Bn capex base.

This is where India can build a real moat. Here are the two companies we’re backing in this space.

HEG: Strengthening India’s Upstream Material Base

HEG is traditionally known for graphite electrodes. That legacy matters because graphite is a critical building block in the battery world. Today, almost every lithium-ion battery in the world uses graphite for its anode. The global anode materials market itself is heading toward the $100 Bn range as battery manufacturing scales up.

India currently imports most of its battery-grade anode materials. This brings cost pressures, exposure to global price swings and vulnerability to supply disruptions. HEG’s move into battery-grade graphite and spherical graphite addresses one of the tightest bottlenecks in the entire value chain.

What makes HEG compelling is not simply the new product line but the capability behind it. They carry decades of manufacturing depth, process control, carbon handling and global export relationships. These foundations matter in sectors where quality, purity and consistency determine competitiveness. HEG is building exactly that foundation. It gives India upstream strength by producing critical processed materials that normally come from abroad. It also opens the door for downstream manufacturers to rely on domestic sources rather than imported supply.

In other words, HEG’s evolution is not a side business. It is a strategic capability for the country.

Lohum: Closing the Loop Through Circular Minerals

If HEG represents the upstream, Lohum represents the downstream and circular loop. The world is waking up to a simple truth: the fastest way to build domestic mineral security is to recycle existing batteries at scale. By 2030, India is expected to generate battery waste that runs into millions of tonnes annually. Waste becomes a resource when companies like Lohum exist.

Lohum’s model is based on recovering high-purity lithium, cobalt, nickel, manganese and graphite from used batteries and production scrap. These recovered materials are then refined into battery-grade inputs again, creating a domestic circular flow of minerals.

Recovered minerals reduce import dependence. They cut exposure to volatile international prices. They bring predictability to cell manufacturers that rely on long-term mineral supply. And they reduce the environmental footprint of new manufacturing.

The strategic logic is even stronger. No country can build large-scale cell manufacturing without stable access to raw materials. Circular supply becomes the most reliable buffer when global supply chains overload.

India’s Policy Push: What Needs to Happen Next

China’s rise was built on policy coordination. India is beginning to move in the same direction. Key initiatives include:

• PLI scheme for cell manufacturing

• 40 GWh of capacity allocated to Reliance, Ola, and others

• National Critical Minerals Mission with a 16,300 crore budget

• 1 lakh crore R&D and Innovation Fund for sunrise sectors

But the missing piece is still the Basic Customs Duty. Solar grew only after India implemented 40% duty on modules and 25% on cells. Battery materials need a similar cost parity push. For cell assembly alone, a 25–30% duty is needed for domestic viability.

Closing Thoughts

The battery ecosystem is moving from a phase of broad optimism to one of hard execution. Demand is real and accelerating, but the supply chain remains uneven, capital intensive, and deeply dependent on technological capability across materials, cell design, and manufacturing. India’s opportunity sits in entering the right nodes of this chain rather than trying to build everything at once. Companies like HEG and Lohum show that competitive strengths can emerge in very specific layers if the focus is sharp and technical depth is built early.

If you prefer reading to watching, this blog has captured the core themes from the conversation. For a fuller experience, you can view the video below.

Read our recent blog on energy transition:

“India’s path to a $10 trillion economy depends on one thing most people never think about: Batteries. With nearly 80% of its oil & half its natural gas coming from abroad, our energy bill has become a drag on economic ambition and even strategic independence. Recent trade skirmishes with the US around energy supply have shown how vulnerable the system is.”

Great intro paragraph. Got my attention. Great read Ty.