India’s Product Nation Moment

Podcast: Why electronics can redefine India’s next decade?

For decades, India has mostly served as the world’s back-office and the world’s factory floor for other people’s brands. We wrote the code, assembled the devices, delivered the services. The real profits sat elsewhere. Global firms like Apple, Samsung, Dell, HP and LG captured the largest share of margins. Indian companies, despite talent and scale, remained in low-value layers such as EMS, assembly & labour-intensive work. But this is now changing.

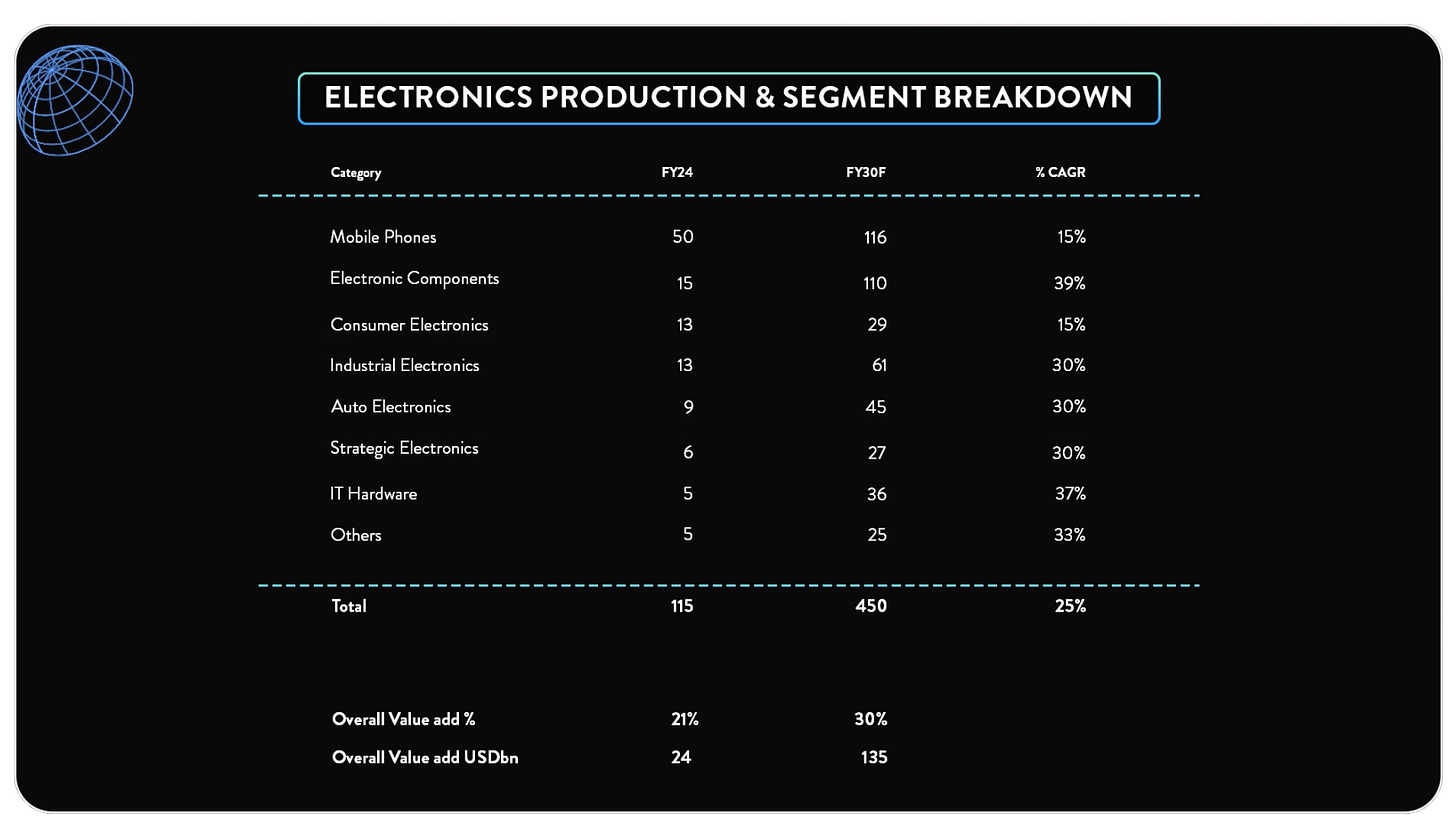

In the last decade, India’s electronics industry has grown from around $45 Bn to more than $115 Bn today. Domestic value addition has improved but is still only around 21%, which shows how large the growth opportunity is. Over the next decade, categories such as smartphones, consumer electronics, automotive electronics, defence electronics, medical devices and components could push the industry towards $450 Bn.

Policy support, supply-chain shifts, strong engineering talent and rising domestic demand have combined to change the trajectory. More importantly, India now recognises that relying on foreign technology is a risk to economic & strategic autonomy.

To understand this transition better, Manish Sharma (Former Chairman Panasonic India) and Sanjay Nayak (Co-founder Tejas Networks, Ex-CEO & MD) joined Yash Kela and Nishchal Mittal from Singularity for a detailed conversation. The insights from their journeys, including near-death moments and long-term learning, offer a real blueprint for what India must solve next.

The Hard Lessons That Built Resilience

Both leaders shared early failures that shaped their thinking.

Manish Sharma’s Lesson: Design Must Match Real-World Conditions

Early in his career at Samsung, Manish Ji spent a year convincing the Russian subsidiary to place export orders from India. After significant effort, Samsung shipped 5,000 televisions, then another 5,000. When the units arrived in Russia, every single TV had hairline cracks.

Initially, the team blamed production. Later, the real problem became clear. The plastic housing used in India could not withstand the sub-zero temperatures during ocean transport. This was not a manufacturing issue but a design oversight.

The lesson was simple yet powerful. Engineering cannot happen in isolation. Design must reflect the customer’s environment and the entire life cycle of the product. Lab success does not guarantee field success.

Sanjay Nayak’s Journey: Surviving Financial Collapse & Natural Disasters

Tejas Networks began in 2000 with an ambitious idea. India had almost no deep-tech hardware ecosystem. Venture capital was limited. Telecom equipment required near-perfect reliability. Global giants dominated the space.

Even then, Sanjay Ji and his co-founders believed India could build world-class telecom products. Tejas grew rapidly for the first seven years, reaching almost ₹700 Cr in revenue and preparing for an IPO. Then the global financial crisis hit. Nortel, which contributed around half of Tejas’s global business, filed for bankruptcy. India’s 2G scam froze domestic capex. Revenue dropped sharply.

The trouble did not end there. A severe cyclone flooded the Pondicherry factory under more than fifteen feet of water. Months later, a fire damaged the Bangalore office building. At one point, Tejas had more cash in the bank than its total market cap around Covid, which reflected how dire the situation had become.

The company survived because it continued investing heavily in R&D even in the worst period. In one year, Tejas spent ₹80 Cr on R&D despite revenue being only around ₹200 Cr. That investment created the next generation of products and helped the company recover and eventually go public.

Why Strategic Autonomy Matters for India

The conversation introduced a clear idea. India cannot afford to rely on foreign technology for systems that power the economy. There are two reasons:

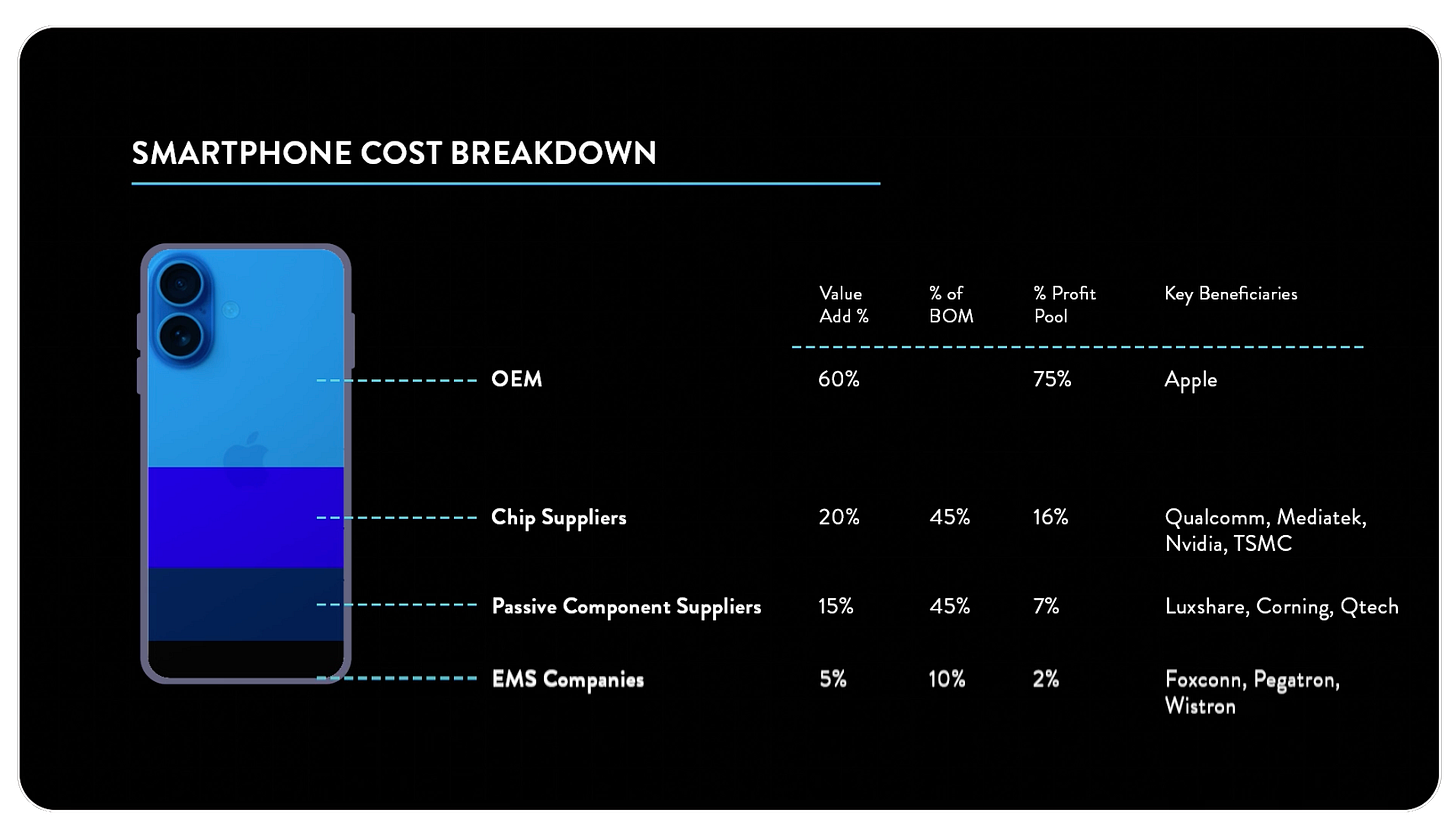

Highest Value Sits With Product Ownership: In electronics, value pools are skewed. If a product costs ₹100, around ₹60 goes to the OEM and they capture 75% of the total profit. The EMS player earns roughly 5% of value and around 2% of the profit. If India does not build product companies, it stays in low-margin, low-value zones.

Technology Denial Could Disrupt the Entire Economy: Most critical technologies used in India are owned outside India. Any major country can restrict access at any time. This can disrupt aviation systems, defence networks, telecom infrastructure, payment systems and logistics. The global environment is shifting rapidly. Countries are protecting their strategic technologies more aggressively. India needs to build its own capabilities in telecom, defence electronics, components and semiconductors to avoid systemic risk.

Semiconductors: India’s Missing Core Layer

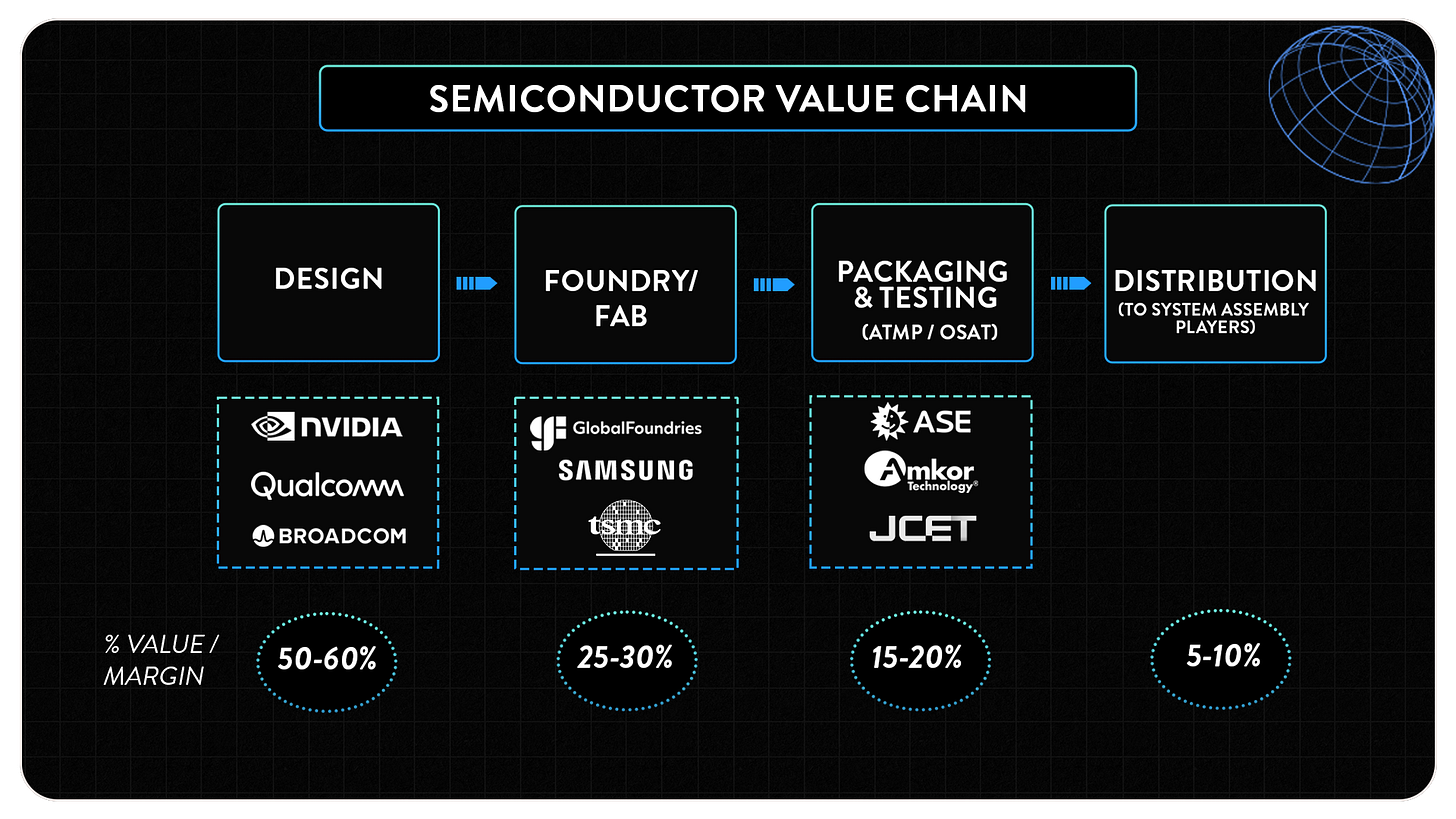

Both Manish Ji and Sanjay Ji highlighted one simple truth. Without semiconductors, there is no real electronics strategy. Chips decide performance, value capture and strategic control.

Today India imports almost all critical chips, which creates three direct problems:

Low margin capture: Chip design and IP hold most of the profit. Assembly captures very little.

Vulnerable supply chain: Any disruption in chip access can stall entire industries.

Limited innovation: If controllers and SoCs come from outside, India cannot build differentiated products.

Where India Should Focus

Rather than trying to immediately build cutting-edge fabs, India should instead concentrate on achievable, high-impact layers:

Chip design and IP: India already has talent and global R&D centres. This is the fastest value-add lever.

Mature-node manufacturing: Nodes like 28nm and 40nm power automotive, defence and industrial electronics. These are realistic starting points.

Discrete and Analog Components: MOSFETs, Power ICs, RF parts and basic analog chips can be localised quickly.

Packaging and testing: OSAT capability is easier to build and supports the full ecosystem.

As Sanjay Ji said, technology denial is now as dangerous as supply disruption. Without semiconductor depth, India stays dependent in telecom, defence, automotive and AI infrastructure.

To truly become a product nation, India must build semiconductor capability step by step, starting where it has the highest leverage.

What Has Worked So Far: The AC Localisation Playbook

One of the strongest success stories is the localisation of air conditioners.

Around 2020, AC penetration in India was only about 5.5%. Local value addition was just 20 to 22%. Most high-value components such as compressors and heat exchangers were imported.

Industry leaders, including Manish Ji, aligned on a strategy. Instead of pushing for PLI on finished ACs, the sector requested PLI on components. This allowed domestic players to manufacture critical items with scale. Manufacturers agreed to aggregate demand, absorb initial cost disadvantages and use PLI incentives to support localisation.

The results have been impressive. In three to four years:

Local value addition has increased from 20% to above 65%

Millions of compressors are now made in India

Most key components are manufactured domestically

Jobs increased due to installation & maintenance needs

This demonstrates what is possible when policy, industry and demand come together with a long-term view.

EMS Evolution: From Assembly to Design Capability

EMS in India initially grew due to state-level VAT and excise incentives. Many firms were formed just to use temporary tax benefits. Many eventually faded away.

However, the successful EMS companies followed a different path. They invested in design and engineering, moved into ODM roles for selected categories and built deeper capabilities across camera modules, PCBs (Printed Circuit Boards) and sub-assemblies.

The future belongs to EMS companies that expand beyond assembly into design-led value addition. Scale is necessary but differentiation is essential.

The $450 Billion Opportunity Ahead

If the electronics sector reaches $450 Bn and India captures even 30% of that value through domestic production, the opportunity is enormous. The highest value sits in design, IP and high-end components. The top five companies in any deep-tech category usually take 80% of the profit pool.

India needs three key ingredients to compete:

End-to-end talent

Hardware engineering, software, firmware, product design, supply chain and global sales need to come together.

Patient capital

Deep-tech takes years to build. It needs sustained funding before revenue arrives.

Strong domestic first market

Government procurement can accelerate adoption and help companies scale early. This is how both the US and China built their local champions.

PCBs & Components: The Big Unlock

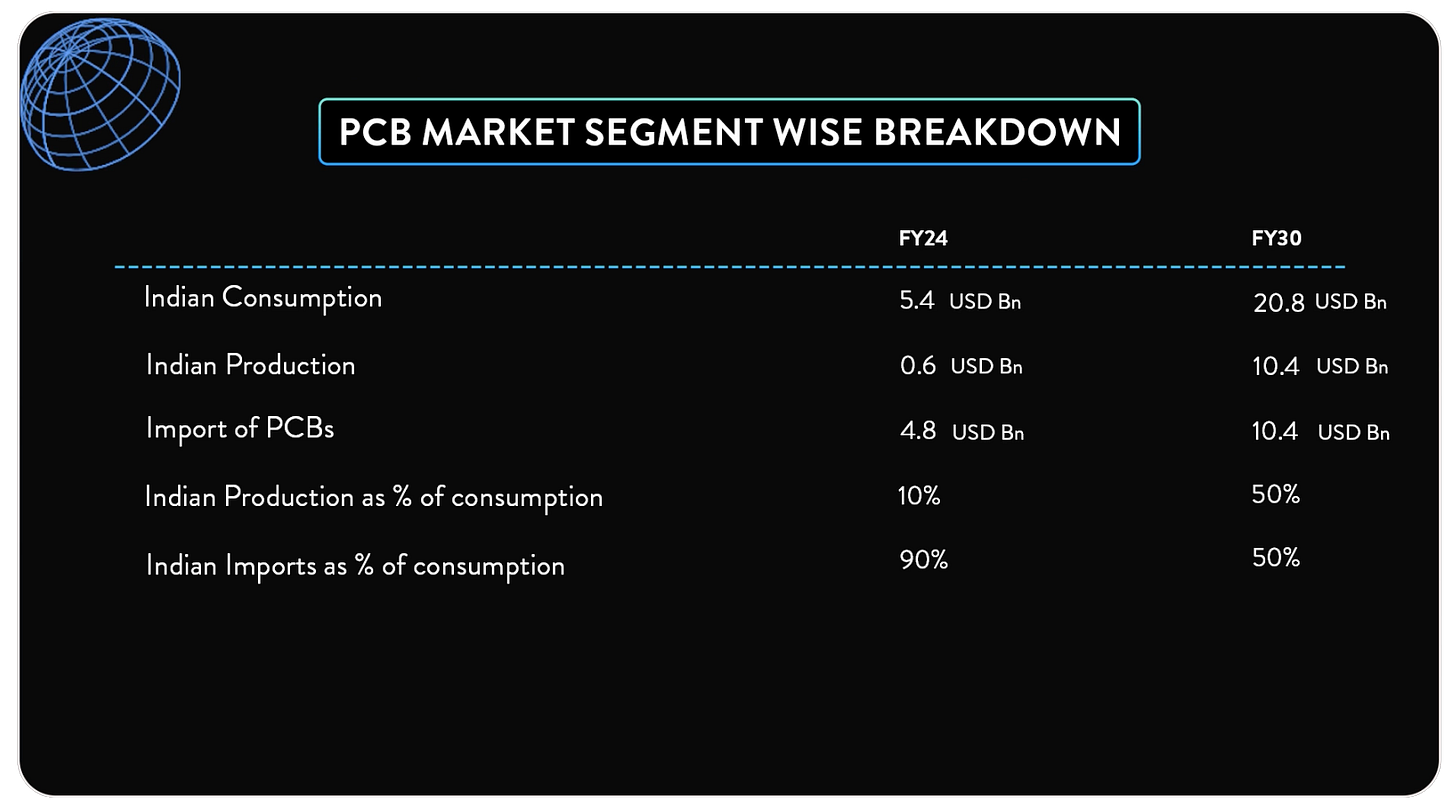

India still imports about $5 Bn worth of bare PCBs/sub-assemblies. Even when final assembly happens domestically, the electronic blocks in some cases arrive pre-assembled from abroad. This makes it difficult to aggregate component demand and slows localisation.

There is now a coordinated effort to fix this. Components India can localise quickly:

PCBs for consumer electronics

Transformers

Heat sinks

Wire harnesses

Basic electromechanical parts

These components cut across categories and represent a growing value pool. If India reaches $450 Bn in electronics production, components alone could become a $110 Bn segment. PCB manufacturing could grow from less than $1 Bn to around $10 Bn. This requires integrated clusters, consistent demand and long-term planning.

Why India Needs Integrated Electronics Clusters

China’s success in electronics came from concentrated clusters where component makers, EMS firms, OEMs and logistics partners were tightly integrated. This improves speed, lowers cost and drives innovation.

India has early examples such as Sri City, but the ecosystem remains scattered. A cluster approach can significantly improve competitiveness in components and subsystems.

High-Potential Export Categories

According to Manish Ji, no category is fully mature yet because technology cycles keep shifting. However, several categories show strong export potential.

Air Conditioners: India has built component capability and manufacturing scale. Export potential is high.

CCTV and Surveillance Systems: Security standards and localisation requirements have reshaped the market. Domestic players are gaining ground and can become exporters.

Defence Electronics: India must build local capability here due to national security requirements. Growth rates are strong.

Small Consumer Electronics: Wearables, small appliances and IoT devices, especially where logistics costs are low.

Components and Subsystems: Heat sinks, transformers, PCBs and power electronics can become strong export categories if scale builds up.

India does not need to reinvent every technology. Mature technologies can be acquired through JV and TOT models. Emerging technologies need deeper R&D and strong domestic teams.

What India Must Do Next

Becoming a product nation requires a coordinated ecosystem. India needs to:

Build products that solve real customer use cases and have large domestic consumption

Cluster component ecosystems for scale

Use government procurement to support early-stage companies

Invest heavily in R&D & IP ownership

Partner with Japan, Korea and Europe for advanced technologies

Acquire overseas companies to accelerate time-to-market

Develop MSMEs that feed into large OEMs and EMS players

Shift mindsets toward long-term product creation

India has the market, talent and policy support. The next decade will determine whether India keeps assembling products for others or builds the world’s next generation of technology champions.

If India succeeds, the electronics sector alone can create lakhs of jobs, generate large export engines and deliver strategic autonomy in areas such as telecom, defence, computing and critical components. This is not only an economic opportunity. It is a national priority.

That’s all for today! We discuss this and way more in the podcast - tune in!

Checkout our recent posts: